From Niue to Niu Silani

By Experience Wellington Digital Content Producer Tom Etuata

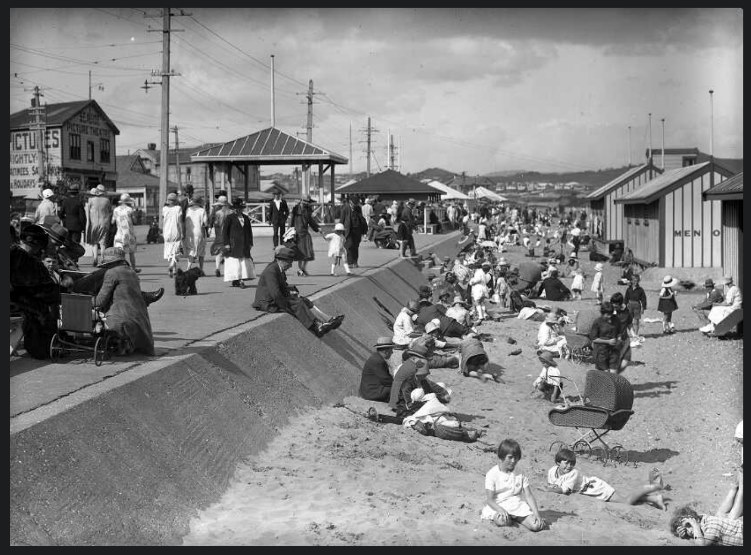

“Labour shortages in the 1960s and 1970s spurred the migration of thousands of Pacific Island people to New Zealand. Many settled in Wellington.” – Te Ara Encyclopaedia of New Zealand

My parents moved from Niue to Niu Silani (New Zealand) in mid 1967.

My Matua Tanē (father) Tom Etuata Snr received an Inland Revenue scholarship to work in Ueligitoni (Wellington) – so he and my Matua Fifine (mother) Akeletama made the decision to move to Niu Silani.

They arrived on the ship SS Tofua which sailed to Niu Silani and docked in Okalana (Auckland). From there they travelled down to Ueligitoni.

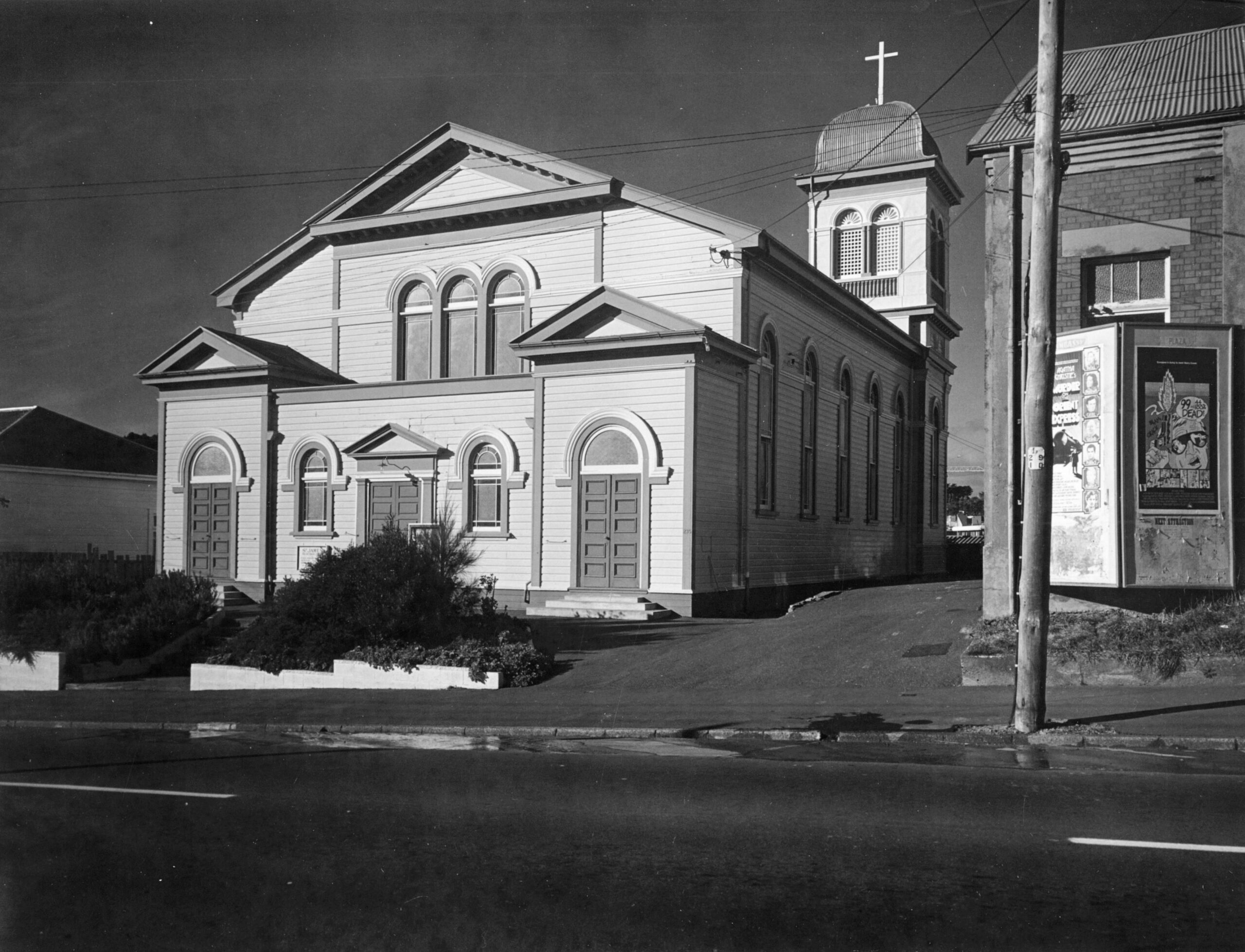

Pasifika families migrating to Ueligitoni supported each other as they settled into a new country. On Aho Tapu (Sunday), some Pasifika families would congregate at the Pacific Island Church (PIC) in Newtown. This place was an important support base in the 1960s, 70s and 80s – not only as a place of worship but also for maintaining ties with other Pasifika families living and settling in Ueligitoni.

By the early 1970s The Niue Maaga (Community) in Ueligitoni was tupuhake (growing). This led to Niuean Minister Reverend Lagi Sipeli and his wife Mokataufoou (Moka) Sipeli arriving from Okolana to Ueligitoni to provide much needed spiritual guidance and support.

It was evident that there wasn’t enough taimi (time) and space for the Niuean community to have their own Fekafekau (Service) at PIC, so in October 1977 the Niuean congregation moved from the PIC Church to Fakalataha (join) the Palagi (European) congregation at St James Presbyterian Church on Adelaide Road, Newtown.

It was a perfect union between the Palagi and Niuean congregations, and both communities prospered. Many Niuean children from that time in the 1980s (including me) remember days of Sunday Schools, White Sunday Services, haircutting ceremonies, big families getting together, big gatherings and even bigger feasts.

In 2013 the St James English Presbyterian Church dissolved and the Niuean congregation moved to St Giles in Kilbirnie. The St James building was considered an earthquake risk and closed for a time, until it was renovated, becoming an up–market apartment complex in 2016.

I went to the first open home of the completed St James apartment complex, curious to see how this once sacred building, where I’d spent most Sundays during childhood, now looked. It had been divided into compartments for luxury living rooms and bedrooms, complete with ensuites. It felt weird, a bit sad and a touch surreal. Other members of the Wellington Niuean community also came along, similarly curious about how the church had been transformed. In a way that day was a Wellington Niuean community reunion of sorts. We reminisced about days gone by, while pointing out to prospective buyers that their beautiful dining and kitchen area was once the spot where the communion table and minister’s pulpit stood.

We Collect Wellington. Tamai e mautolu a Ueligitoni.

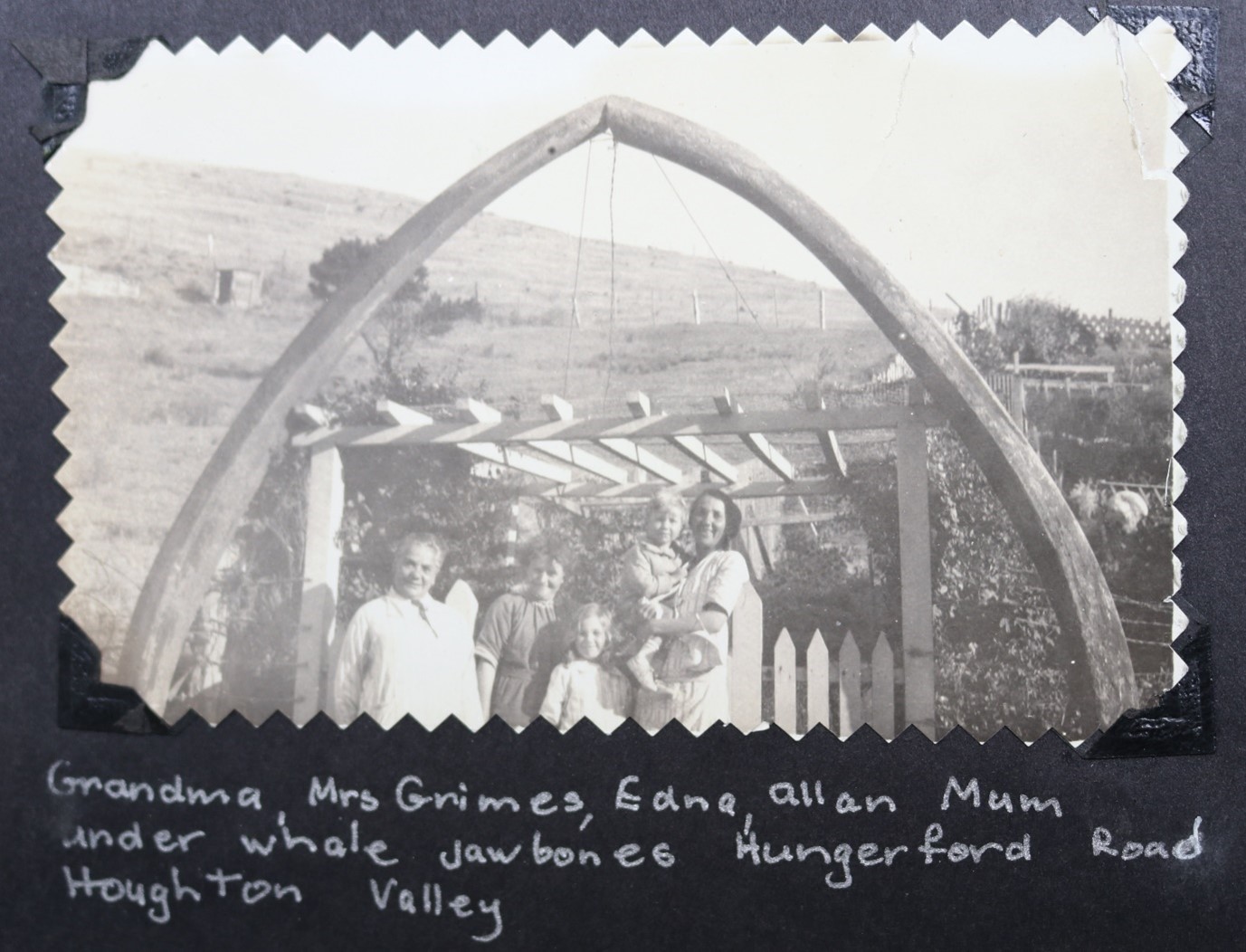

Mokataufoou (Moka) Sipeli has been involved with the Wellington Niuean community from the early 1970s.

Along with her husband the Rev Lagi Sipeli, they both served the Niue community for 34 years retiring from ministry in 2004. Four years later, in 2008, Lagi passed away.

Moka is the matriarch of the Wellington Niuean community and resides in Haitatai. She’s a strong advocate of Takiofa (preserving) the Niuean language. She created the first Niuean Language Nest in New Zealand in 1984 and received the Order of Service Medal in 2018 for service to the Niuean community.

She has kindly donated two of her church Pulou (hats) to Wellington Museum’s collection, which will be on display in future, to help us share the story of the Niuean community. She wore these hats when attending services at both St James and PIC churches. Pulou (hats) are worn by Niuean women when they attended church services as a sign of Fakalilifu (respect).

Fakaaue Lahi (Big Thank You) to Moka Sipeli for kindly donating these hats to

Ueligitoni Fale fakataataa tau tufuga tuai (Wellington Museum).