The rebuilding of Tapu Te Ranga Marae, Paekawakawa (Island Bay)

By Lawrence Wharerau

The basis of it all, is you shift because the grass is greener and the grass was green in Wellington.

Bruce Stewart, Tapu Te Ranga Marae, 1996

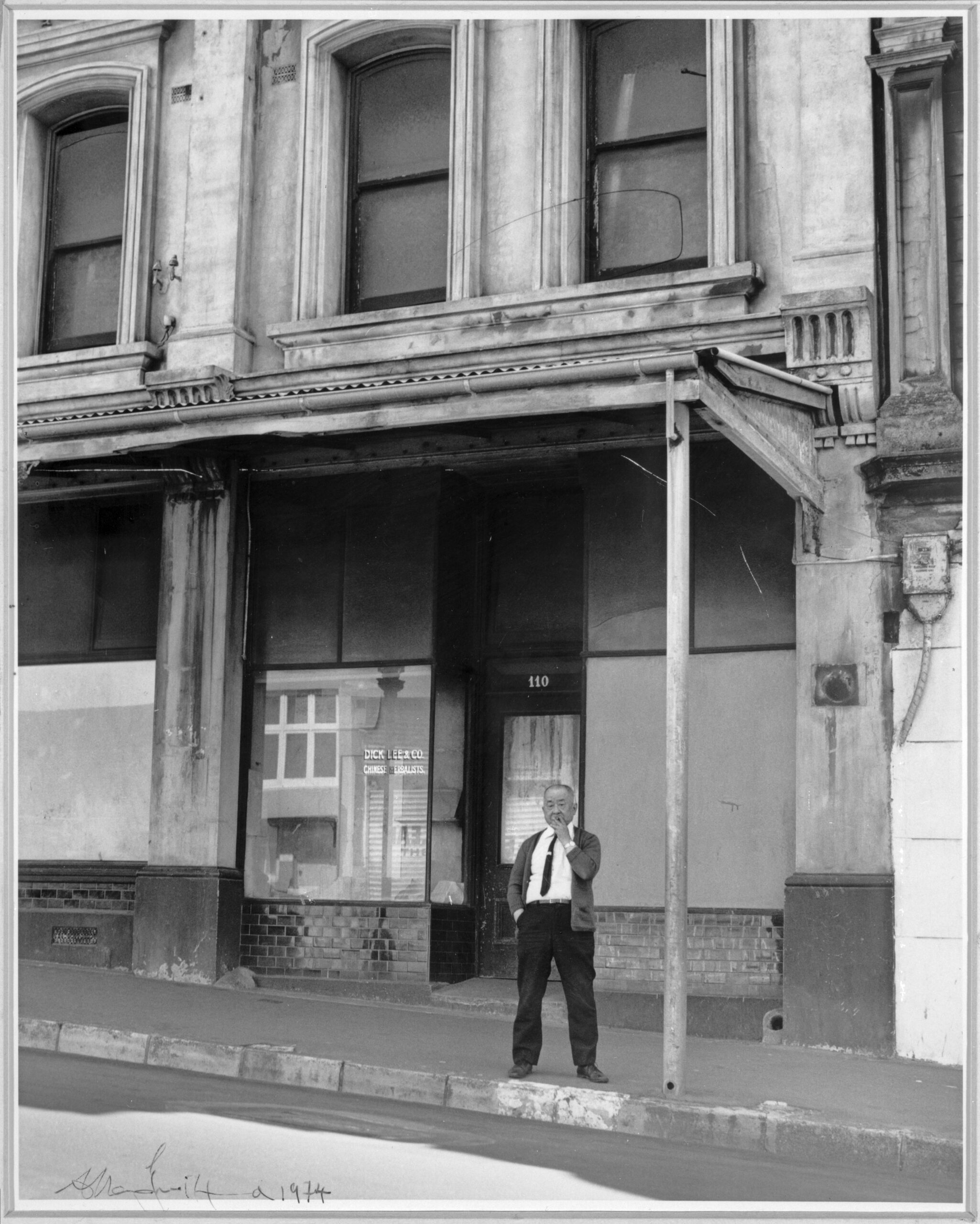

In the early to mid-1970s, with time on his hands to contemplate his next direction in life, Bruce Stewart had a vision to create a space for “the down and outs, the nobodies…” where they could take stock of their situation and recalibrate their lives. To provide shelter and comfort for the homeless, the ex-prisoner, the gang member looking to change their ways, the street kids, the desperate and those living on the fringe of society. This vision led to the building of the innovative Tapu Te Ranga Marae in Paekawakawa, Island Bay.

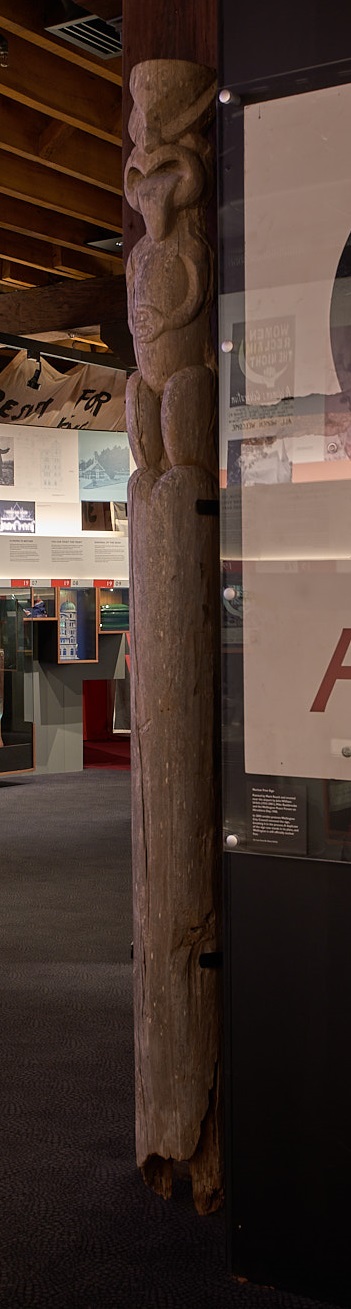

Built almost entirely from recycled materials and creative imagination, Tapu Te Ranga Marae has provided shelter for thousands of people over the

years – people who needed to momentarily step out of the race.

The impressive and unique structure incorporating ten different whare over nine levels was dedicated to women and especially to the mother Bruce, to his shame, often denied in his childhood. His mother, Hinetai Hirini, was of Ngāti Raukawa whakapapa.

Another dream Bruce initiated was to create a sanctuary for birds and plants; an island pā. This saw thousands of plants reared at the marae nursery planted over the 50 hectares of hilly country surrounding the complex. Bruce strongly believed in the principle of ahi kā and of giving back. He felt that we each have a responsibility to make a better world and to protect the environment.

He certainly had his naysayers and doubters. It was with determined grit, commitment and passion that Bruce pushed on to achieve his vision, to a level some considered arrogance. His unconventional approach often saw him butt heads with authorities and earned him several visits from local council building and health inspectors. Nonetheless he continued, determined to complete his dream.

When he passed away in June 2017 this passion was picked up by his whānau and staunch supporters to continue his legacy. He was buried at a spot overseeing his dream.

Almost two years later, to the day, the complex was razed to the ground in a tragic accident that saw only the nursery shed survive the inferno.

Fire inspectors discovered that an unattended brazier, that was believed to have been doused, was fanned back to life by a steady breeze which saw embers blow into the downstairs laundry area, sparking the tragic fire.

Bruce’s daughter Pare was in labour when the fire was discovered and in the time it took her to get from her home next door to the marae, the complex was already beyond saving. All available fire units from Palmerston North south were scrambled to contain the fire and keep it from spreading to neighbouring properties.

Two years later, Pare, her whānau and supporters are still dead set and committed to rebuilding Tapu Te Ranga Marae from the ground up. This time, with the support of neighbours, council, government and sponsors, they are keen to reconstruct the complex with the required resource consents and compliance.

For the Stewart whānau, Tapu Te Ranga Marae was more than a marae, it was a huge commitment, with the complex also serving as their home, their church, their university – the place they could receive guests from far and wide and share Bruce’s philosophy of giving back to the birds and trees.